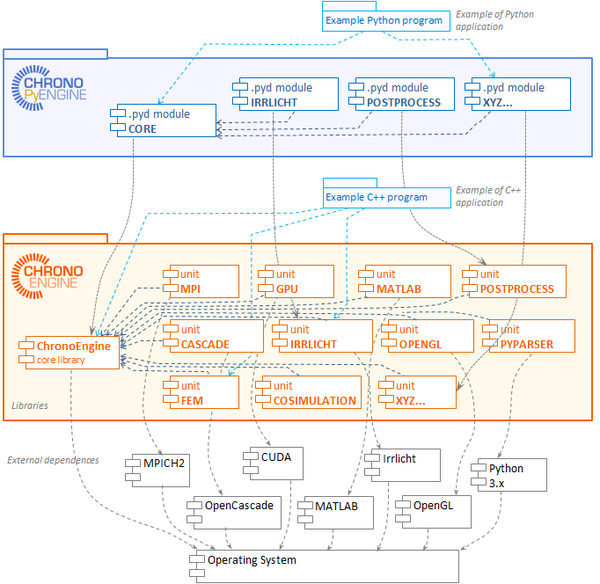

PyChrono is a Python wrapper for Chrono. It is a set of Python modules that correspond to units of Chrono, as shown in this scheme:

Differences between Python and C++

Not all the functionalities of the C++ API can be mapped 1:1 to the Python API, of course. Python is an interpreted language that differs from C++ for many reasons, so there are some differences and limitations, but also advantages. If you already used the C++ API of Chrono, you will find that this documentation is useful for easily jumping into the PyChrono development.

Object creation

In C++ you can create objects in two ways: on the stack and on the heap (the latter is used for dynamic allocation). For example, respectively, this is object creation in C++ language

In the second case, in C++ you must remember to deallocate the object with delete (my_system_pointer) soon or later. In Python, object creation is always done in a single way: objectname = namespace.classname() , and it does not require that you remember to delete an object, because the lifetime of an object is automatically managed by Python. So object creation in Python is simply:

Note that the = operator in Python does not mean copy (except for simple types such as integers, floats, etc.) but means assign, so for example

will output 2, because you created a single ChSystem object, with two handles pointing to it.

Templated classes

Currently there is no support for templated classes in Python. So, all the C++ classes relying on templates need to be wrapped in Python in order to provide the most relevant specializations. Since the most fundamental templated classes offer aliases for the most common specialization those names are reflected also in the Python wrapper.

There is a (quite limited) support for templates of templates, especially for the std::vector<> container. The concept is the same: the C++ template is translated in a special name in Python. For std::vector, we prepend the vector_ prefix:

ChVector x y z members

In C++ you access the x y z components of a 3D vector using the functions x() y() z(), that return a reference to the components. To avoid some issues, we drop the () parentheses and we mapped these functions to direct access to x y z class members in Python, so:

becomes

A similar concept is applied for quaternions components e0 e1 e2 e3, eg. one uses myquaternion.e0 in Python, instead of myquaternion.e0() in C++.

Shared pointers

Except for vectors, matrices, etc., most of the complex objects that you create with the Chrono API are managed via C++ shared pointers. This is the case of ChBody parts, ChLink constraints, etc. Shared pointers are a C++ technology that allows the user to create objects and do not worry about deletion, because deletion is managed automatically. In the Chrono C++ API such shared pointers are based on templates; as we said previously templates are not supported in Python, but this is not an issue, because PyChrono automatically handle objects with shared pointers if necessary PyChrono.

This is an example of shared pointers in C++ :

This is the equivalent syntax in Python :

my_link_other = my_link_BC etc. Downcasting and upcasting

Upcasting

Upcasting of derived classes to the base class works automatically in Python and does not require intervention. We managed to do this also for shared pointers. For example ChSystem.Add() requires a (shared)pointer to a ChPhysicsItem object, that is a base class, but you can pass it a ChBody, a ChLinkLockGear, etc. that are derived classes. The same in Python.

Downcasting

A bigger problem is the downcasting of base classes to derived classes. That is, if a function returns a pointer to a base class, how to understand that a specific returned object belongs to a derived class? At the time of writing, an automatic downcasting is performed only for classes inherited from ChFunction and ChAsset. Otherwise, one has to perform manual downcasting using the CastToXXX() helper functions; this is a bit similar to the dynamic_cast<derived>(base) method in C++. Currently such casting functions are provided for many shared pointers. Use this in Python as in the following example:

Nested classes

SWIG does not currently support nested classes in Python (see http://www.swig.org/Doc4.0/SWIGPlus.html#SWIGPlus_nested_classes). Nested classes can be either ignored or, such as in PyChrono, flattened. This is automatically done for every nested class in Chrono. This means that PyChrono equivalents of nested C++ classes will be in the upper namespace level, as you may see in the following example:

In Python we have:

Not supported classes

We managed to map in Python most of the C++ classes of common interest, but maybe that there are still some classes or functions that are not yet mapped to Python. This can be understood in the following way. Functions that are correctly mapped will return objects whose type is echoed in the interpreter window as:

A function that is not yet mapped, for instance ChSystem.GetSystemDescriptor(), will give a shorter echo, that represents the type information for a pointer to an object that is unusable in Python:

Demos and examples

You can find examples of use in these tutorials