Table of Contents

This documentation component introduces important concepts used through the entire Chrono API for managing coordinates, points, transformations and rotations.

Vectors

Vectors that represent 3D points in space are defined by means of the chrono::ChVector class. In mathematical notation:

\[ \mathbf{p}=\{p_x,p_y,p_z\} \]

The ChVector<> class is templated. One can have vectors with single precision, as ChVector<float>, with double precision, as ChVector<double>, etc. The default data type is double precision; i.e., ChVector<> defaults to ChVector<double>.

Example, creating a vector:

Add, subtract, multiply vectors, using +,-,* operators.

Chrono offers also an useful set of constant (double) vectors - VNULL, VECT_X, VECT_Y, VECT_Z, that represent the null and the axes unit vectors respectively.

Quaternions

Quaternions, which provide a number system that extends complex numbers, are used is Chrono to represent rotations in 3D space. The Chrono implementation of quaternions is encapsulated in the chrono::ChQuaternion class. In mathematical notation, a quaternion is represented as a set of four real numbers:

\[ \mathbf{q}=\{q_0,q_1,q_2,q_3\} \]

Quaternion algebra properties:

- A real unit quaternion \( \mathbf{q}=\{1,0,0,0\} \) represents no rotation

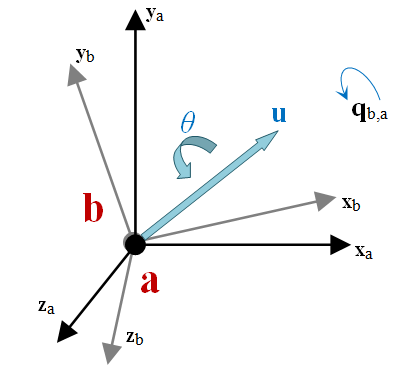

Given a rotation \( \theta_{u} \) about a generic unit vector \( \mathbf{u} \), the corresponding quaternion is

\[ \mathbf{q}=\left\{ \begin{array}{c} \cos(\alpha_u / 2)\\ {u}_x \sin(\theta_u / 2)\\ {u}_y \sin(\theta_u / 2)\\ {u}_z \sin(\theta_u / 2) \end{array} \right\} \]

Only quaternions with unit norm represent valid rotations. Quaternions can be built in different ways.

Examples of building an equivalent quaternion that represents no rotation:

The quaternion as a function of a rotation

\( \theta_{u} \) about a generic unit vector \( \mathbf{u} \) can be build with:

The rotation of a point by a quaternion can be done easily by using the .Rotate() member function of quaternions. The example below shows how to rotate a point 20 degrees about y-axis:

The * operator is used to perform a quaternion product. From a kinematic perspective, this represents concatenation of rotations.

Example: a rotation qc followed by a rotation qb can be shortened in a single qa, if qa, qb, and qc are quaternions, as follows:

Alternatively, the >> operator concatenates from left to right:

Rotation matrices

A rotation matrix \( \mathbf{A} \) is used in Chrono to characterize the 3D orientation of a reference frame with respect to a different reference frame. Most of the implementation support related to the concept of rotation matrix is encapsulated in chrono::ChMatrix33. There are Chrono functions that given a quaternion produce a 3x3 orientation matrix \( \mathbf{q} \mapsto \mathbf{A} \) and viceversa \( \mathbf{A} \mapsto \mathbf{q} \). Note that a rotation matrix is an orthnormal matrix, \( \mathbf{A} \in \mathsf{SO}(3) \). Therefore, \( \mathbf{A}^{-1} = \mathbf{A}^{t} \)

Creating a rotation matrix:

The * operator can multiply two rotation matrices, for instance a rotation mA followed by a rotation mB becomes:

The * operator can multiply a ChVector<>, this corresponds to rotating the vector:

The inverse rotation is the inverse of the matrix, which is also the transpose.

ChCoordsys

A chrono::ChCoordsys represents a coordinate system in 3D space. It embeds both a vector (coordinate translation \( \mathbf{d} \) ) and a quaternion (coordinate rotation \( \mathbf{q} \) ):

\[ \mathbf{c}=\{\mathbf{d},\mathbf{q}\} \]

The ChCoordys is a lightweight version of a ChFrame, which is discussed next.

ChFrame

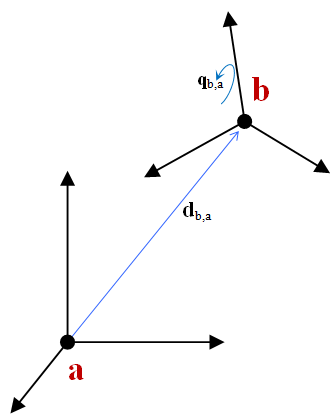

A chrono::ChFrame represents a coordinate system in 3D space like ChCoordsys but includes more advanced features.

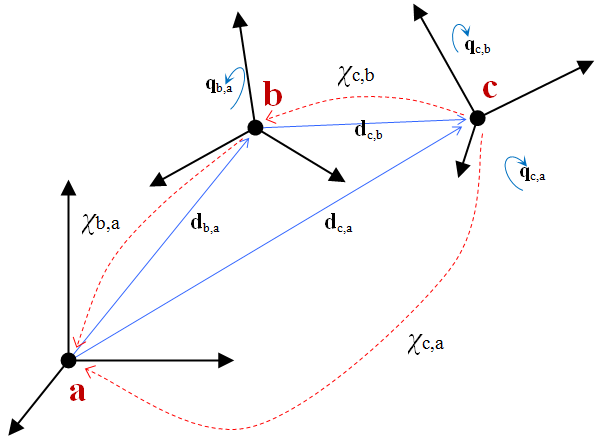

As shown in the picture above, a ChFrame object indicates how "rotated" and "displaced" a coordinate system b is with respect to another coordinate system a Many time a is the absolute reference frame.

\[ \mathbf{d}_{a,b(c)} \]

is used to define a vector \( \mathbf{d} \) ending in point \( a \), starting from point \( b \), expressed in the base \( c \) (that is, measured along the x,y,z axes of the coordinate system \( c \) ). If \( b \) is omitted, it is assumed to be the origin of the absolute reference frame.As a ChCoordsys, a ChFrame object has a vector for the translation and a quaternion for the rotation:

\[ \mathbf{c}=\{\mathbf{d},\mathbf{q}\} \]

As an alternative to the quaternion a ChFrame object also stores an auxiliary 3x3 rotation matrix that can be used to speed up computations where quaternions would be less efficient.

ChCoordsys can be considered as a lightweight version of ChFrame. To save memory or if advanced features are not needed, ChCoordsys<> can be a better choice.

There are several ways to build a ChFrame. For instance:

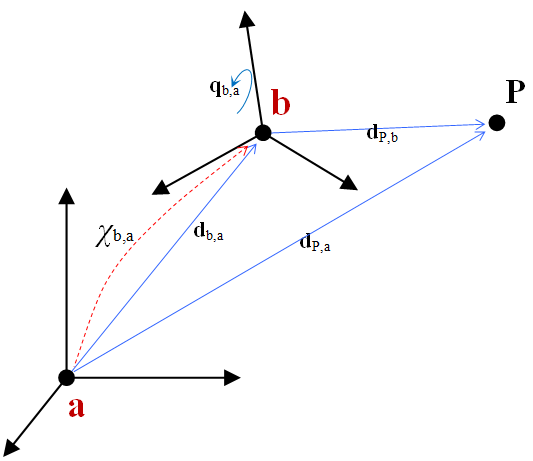

One of the most important features of a ChFrame object is the ability to transform points and other ChFrame objects.

Example: Transforming a point from a local coordinate system b to the absolute coordinate system a:

Usually an affine transformation involving rotation by a matrix A and a translation is used:

\[ \mathbf{d}_{P,a(a)}=\mathbf{d}_{b,a(a)} + \mathbf{A}_{ba} \mathbf{d}_{P,b(b)} \]

This can be done in Chrono as follows:

However, the ChFrame<> class makes this simpler:

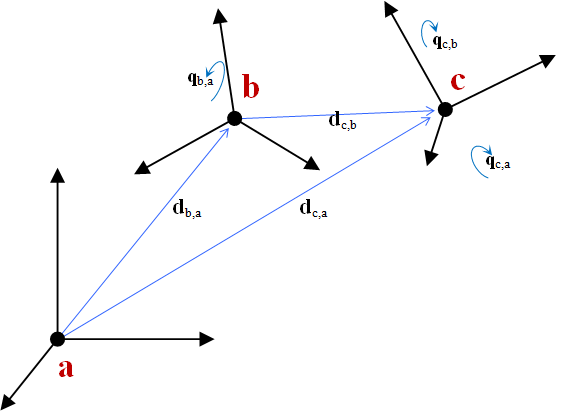

The same concept can be used to chain coordinate transformations. For instance, if the transformation from a frame c to b and from b to a is known, then the total frame rotation and displacement can be found.

This translates into working with a less complex representation. Symbols are recycled to emphasize that the latter formalism has the same meaning insofar using the displacements and quaternions:

The transformation above can be expressed with an alternative operator >>, whose operands are swapped with respect to the * operator:

... using the * operator RIGHT TO LEFT transformations, as in:

X_ca = X_ba * X_cb ... using the >> operator LEFT TO RIGHT transformations, as in:

X_ca = X_cb >> X_ba ... it is more 'intuitive' (see how the subscripts cb-ba follow a 'chain')

... if the first operand is a vector, as in

vnew = v >> X_dc >> X_cb >> X_ba, The default behavior of the compiler is to perform operations from the left, leading to a sequence of matrix-by-ChFrame operations returning temporary vectors. Otherwise, the * operator would create several ChFrame<> temporary objects, which would be slower.

One can also use the * or >> operators with other objects, for example using >> between a ChFrame Xa and a ChVector vb. The outcome of this operation is a new ChFrame object obtained by translating the old one by a vector vb:

The same holds for in-place operators *= or >>=, which can be used to translate or to rotate a ChFrame, or to transform entirely, depending on how it is used: with a ChVector or a ChQuaternion or another ChFrame. For example, to translate Xa by vector vb one writes:

Note that while the operators * and >> create temporary objects, that is not the case with *= or >>=, which leads to improved efficiency. In this context, a rule of thumb is to avoid:

- Operators * and >>

- Use of low-level functions such as TransformLocalToParent, TransformParentToLocal, etc.

Both the * and >> operations support an inverse transformation. Example: in the relation X_ca = X_cb >> X_ba; supposed that X_ca and X_cb are known and one is interested in computing X_ba. Pre-multiplying both sides of the equation by the inverse of X_cb yields

Note that the GetInverse operation might be less efficient than the less readable low-level methods, in this case TransformParentToLocal(), that is:

See chrono::ChFrame for API details.

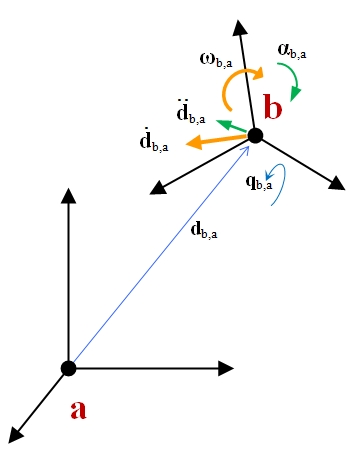

ChFrameMoving

The chrono::ChFrameMoving object represents a coordinate system in 3D space, like a ChFrame, but it stores also information about the velocity and accelerations of the frame:

\[ \mathbf{c}=\{\mathbf{p},\mathbf{q},\dot{\mathbf{p}}, \dot{\mathbf{q}}, \ddot{\mathbf{p}}, \ddot{\mathbf{q}} \} \]

Note that using quaternion derivatives to express angular velocity and angular acceleration can be cumbersome. Therefore, this class also has the possibility of setting and getting such data in terms of angular velocity

\( \mathbf{\omega} \) and of angular acceleration \( \mathbf{\alpha} \) :

\[ \mathbf{c}=\{\mathbf{p},\mathbf{q},\dot{\mathbf{p}}, \mathbf{\omega}, \ddot{\mathbf{p}}, \mathbf{\alpha}\} \]

This can be shown intuitively with the following picture:

Note that 'angular' velocities and accelerations can be set/get both in the basis of the moving frame or in the absolute frame.

Example: A ChFrameMoving is created and assigned a non-zero angular velocity and linear velocity, also linear and angular accelerations are assigned.

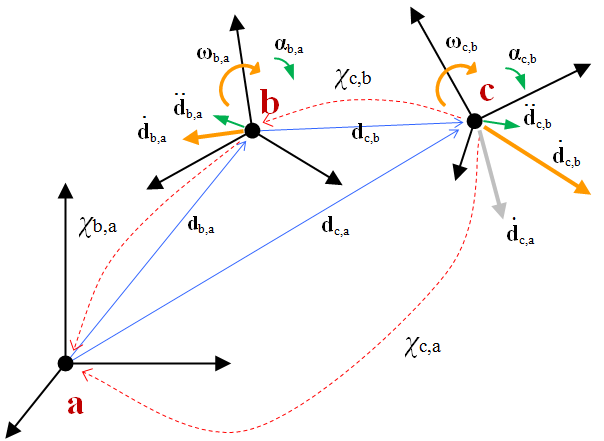

A ChFrameMoving can be used to transform ChVector (points in space), a ChFrame, or ChFrameMoving objects. Velocities are also computed and transformed.

Example: The absolute velocity and angular velocity of c with respect to a can be computed if the transformation from b to a and from c to b is known:

The case above translates in the following equivalent expressions, using the two alternative formalisms (Left-to-right based on >> operator, or right-to-left based on * operator):

This is exactly the same algebra used in ChFrame and ChCoordsys, except that this time also the velocities and accelerations are also transformed.

Note that the transformation automatically takes into account the contributions of complex terms such as centripetal accelerations, relative accelerations, Coriolis acceleration, etc.

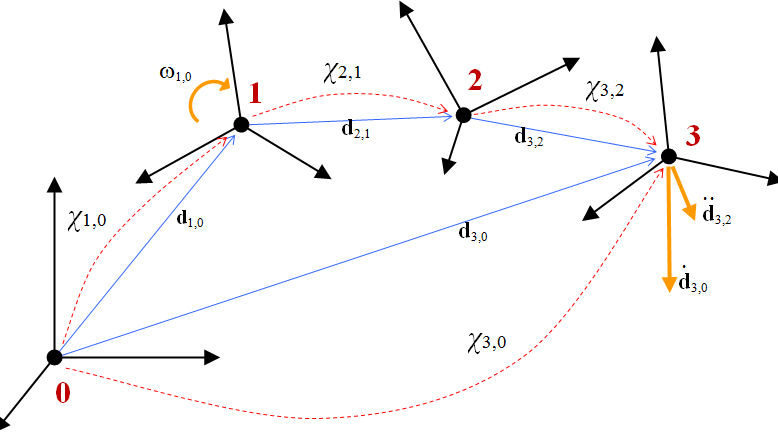

The following is another example with a longer concatenation of transformations:

Note that one can also use the inverse of frame transformations, using GetInverse(), as seen for ChFrame.

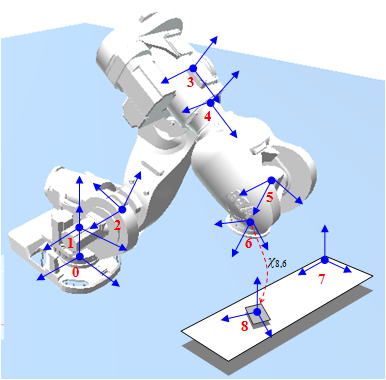

Example: Computing the position, velocity and acceleration of the moving target 8 with respect to the gripper 6, expressed in the basis of the frame 6.

How would one compute X_86 knowing all others? Start from two equivalent expressions of X_80:

X_86>>X_65>>X_54>>X_43>>X_32>>X_21>>X_10 = X_87>>X_70;

also:

X_86>>(X_65>>X_54>>X_43>>X_32>>X_21>>X_10) = X_87>>X_70;

Post multiply both sides by inverse of (...), remember that in general

- X >> X.GetInverse() = I

- X.GetInverse() >> X = I,

where I is the identity transformation that can be removed, to finally get:

Example, based on the same figure: Computing velocity and acceleration of the gripper with respect to the moving target 8, expressed in the basis of reference frame 8.

See chrono::ChFrameMoving for API details.

Theory

Additional details on the theoretical aspects of coordinate transformations in Chrono: